Constanze Mozart in Baden bei Wien

🌿 A Spa Town, a Farewell, a Mystery

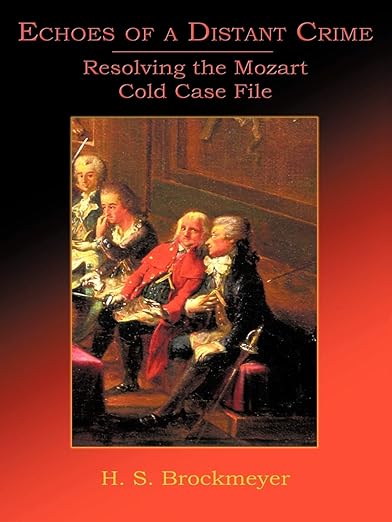

By H. S. Brockmeyer

The deep, resonant tones of the Pummerin bell in St. Stephen’s Cathedral may have inspired Mozart’s compositions for bass voices, particularly Sarastro in The Magic Flute. As he lived near the cathedral in his final year, the profound sound of the bell might have shaped his musical imagination, infusing his works with a depth that echoes through time.

"You cannot imagine how I have been aching for you all this long while. I can’t describe what I have been feeling — a kind of emptiness, which hurts me dreadfully."

Abstract

In the summer of 1791, just months before Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart’s untimely death, his wife Constanze took refuge in the serene spa town of Baden bei Wien. Sent there to recover from illness and a difficult pregnancy, she became a regular at the famed thermal baths. Yet behind the healing waters and peaceful walks lay a deeper, more turbulent story: suspicions, secrets, and a final summer that would never return. In this vivid and historically rich account, H. S. Brockmeyer reconstructs Constanze’s last months with Mozart, her relationship with Franz Xaver Süssmayr, and the layered emotional world of a woman poised between love, loss, and survival.

Baden bei Wien: The Healing Retreat

Constanze Mozart first visited Baden in 1789 after a fall and illness. Prescribed 60 thermal baths by her physician, she returned there every summer through 1791. The spa town, with its Roman origins and sulphurous springs, became her sanctuary — a place to escape the oppressive heat and stress of Vienna, and later, the site of deeply personal events that would define her final summer with Mozart.

A Composer on the Road

While Constanze recovered in Baden, Mozart embarked on a concert tour with Prince Lichnowsky, hoping for financial relief. Despite noble receptions and musical success, the tour ended in disappointment. Mozart blamed Lichnowsky for debts and poor concert returns, noting bitterly: “From the point of view of applause and glory this concert was absolutely magnificent, but the profits were wretchedly meagre.”

“Find Her a Ground-Floor Room”

Mozart was attentive even from afar. In a letter to Anton Stoll, he requested an apartment for Constanze close to the baths, preferably “on the ground floor.” Her accommodation was eventually secured on Renngasse — today still known as the “Mozart Hof”. There, Mozart composed the Ave verum corpus in June 1791 and often joined his wife for brief visits, working in a garden attic room.

Letters from a Lonely Genius

Throughout the summer, Mozart’s letters to Constanze reveal emotional strain, health concerns, and deep longing. He fretted over her bathing routines, warned against slippery floors, and lamented the distance that separated them: “Even my work gives me no pleasure… because I am accustomed to stop working now and then and exchange a few words with you.”

Shadows in Paradise: The Süssmayr Affair

One shadow loomed large: Franz Xaver Süssmayr. As Mozart’s copyist and frequent companion to Constanze, his presence in Baden sparked both suspicion and jealousy. Mozart’s letters oscillate between humor and hostility: “Give Süssmayr a few sound boxes on the ear from me… it would be a good thing if you were to leave a bump on his nose.”

Later biographers — including Ludwig Hildesheimer — have questioned the nature of Constanze’s relationship with Süssmayr. Her own words, years later, suggest a complex, possibly bitter end to their connection.

A Town of Echoes and Memories

Brockmeyer describes Baden in rich detail — its leafy parks, the women’s bathhouse (now a museum), the Rosarium with 800 varieties of roses. She imagines Constanze wandering through ruins, gathering wildflowers, resting under trees, and savoring moments of calm before everything changed.

Paradise Lost

Mozart died on 5 December 1791. Süssmayr, present at his deathbed, vanished shortly after — never to return to Constanze’s life. In the aftermath, her letters show bitterness and avoidance, while he pursued his career. Whatever bond had formed in Baden, it evaporated with the winter frost.

Final Reflections

Constanze’s spa retreat was not just about health. It was about escape, identity, and perhaps the last flicker of freedom before tragedy and reinvention. In Brockmeyer’s hands, this story becomes more than biography — it becomes a portrait of a woman at the threshold of history.

You May Also Like

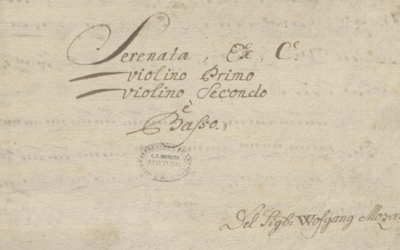

Mozart’s Serenade? A New Discovery? Really?

In Leipzig, what was thought to be a new autograph of Mozart turned out to be a questionable copy. Why are such rushed attributions so common for Mozart, and why is it so hard to correct them when proven false?

Mozart’s K 71: A Fragment Shrouded in Doubt and Uncertainty

Mozart’s K 71, an incomplete aria, is yet another example of musical ambiguity. The fragment’s authorship, dating, and even its very existence as a genuine Mozart work remain open to question. With no definitive evidence, how can this fragment be so confidently attributed to him?

Unpacking Mozart’s Early Education

The story of Ligniville illustrates the pitfalls of romanticizing Mozart’s early life and education, reminding us that the narrative of genius is often a construct that obscures the laborious aspects of musical development.

The False Sonnet of Corilla Olimpica

Leopold Mozart’s relentless pursuit of fame for his son Wolfgang led to questionable tactics, including fabricating a sonnet by the renowned poetess Corilla Olimpica. This desperate attempt to elevate Wolfgang’s reputation casts a shadow over the Mozart legacy.

Mozart’s K 73A: A Mystery Wrapped in Ambiguity

K.143 is a prime example of how Mozart scholarship has turned uncertainty into myth. With no definitive evidence of authorship, date, or purpose, this uninspired recitative and aria in G major likely originated elsewhere. Is it time to admit this is not Mozart’s work at all?

A Farce of Honour in Mozart’s Time

By the time Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart received the Speron d’Oro, the once esteemed honour had become a laughable trinket, awarded through networking and influence rather than merit. Far from reflecting his musical genius, the title, shared with figures like Casanova, symbolised ridicule rather than respect.